Organology & symbolic

Texts, photos, videos: © Patrick Kersalé 1998-2019, except special mention.

See also ...

The “Lesson of the three strings”

The arak ensemble of the Wat Reach Bo

The chapei players, by Émile Gsell

The chapei of the Musée de la Musique of Paris

How to recognize a chapei at first glance?

What are the chapei's characteristics to identify it at a glance?

- The chapei is a long-necked lute with high frets. There, in the world, many long-necked low-fretted lutes (like guitar) —Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Iran ...— but few high-frets ones. The Vietnamese đàn đáy, for example, is a long-necked lute on the half of which only are glued 10 to 12 frets.

- The head of the chapei is characteristic; that of modern instruments is short and comparable to those of the Chinese lutes of the Qing period (1644-1912). Before the Second World War, however, the chapei had a head up to 70 cm, which made them unique.

- Numbers of long-necked lutes have small pyriform soundboxes. That of the chapei is large and flat, of trapezoidal, rectangular or oval shape. These characteristics, associated with the long neck, allows a certain identification.

If the chapei is so recognizable at first glance, it exists nonetheless differences related to its history and the many manufacturers that produced them. These differences affect all the constituent parts: the soundbox, the tailpiece, the neck, the frets, the nut, the pegs and the summit part.

What initially strikes when comparing the ancient and contemporary chapei is the aesthetics of its top part (head) that differentiates it from all others.

The slideshow below offers a sample of professional instruments dating from the last quarter of the 19th century to the present day, as well as instruments dedicated to the tourist market.

General

The various component of the chapei have a reason to be both technical and symbolic. On the organological level, this instrument has the characteristics that define the lute according to the Western meaning: “A soundbox whose role is to amplify the vibration of the strings, a fretboard in the plane of the soundboard, pegs to stretch the strings, a tailpiece where the base of the strings attaches, and strings parallel to the neck”. The head and the frets are options not shared by all the lutes.

The symbolism of each organological component of the chapei is directly related to the Khmer culture, especially its religious culture which makes communicate animism, Brahmanism and Buddhism. The latter is the official religion of the Kingdom of Cambodia whose motto is “Nation, Religion, King” even if there are other religious currents accepted, including Islam and Christianity for the most representative. The Khmer Theravada Buddhism is integrative. It began to spread as early as the 14th century and incorporated the animist and Brahmanic beliefs. This integration exists until now and is visible everywhere in the country: everyday objects, habitat, monasteries, funerary monuments, state buildings, musical instruments and, in the case that interests us here, the chapei. We will describe, in the chapters below, each component of the chapei from the organological and symbolic point of view.

Khmer terminology

The Khmer terms which name the various parts of a chapei sometimes offer variants; we have mentioned, in the picture below those most commonly used. For more information, we invite you to read our Glossary.

English terminology

To facilitate reading and understanding of the organology of the chapei, we borrowed English terms used for the guitar.

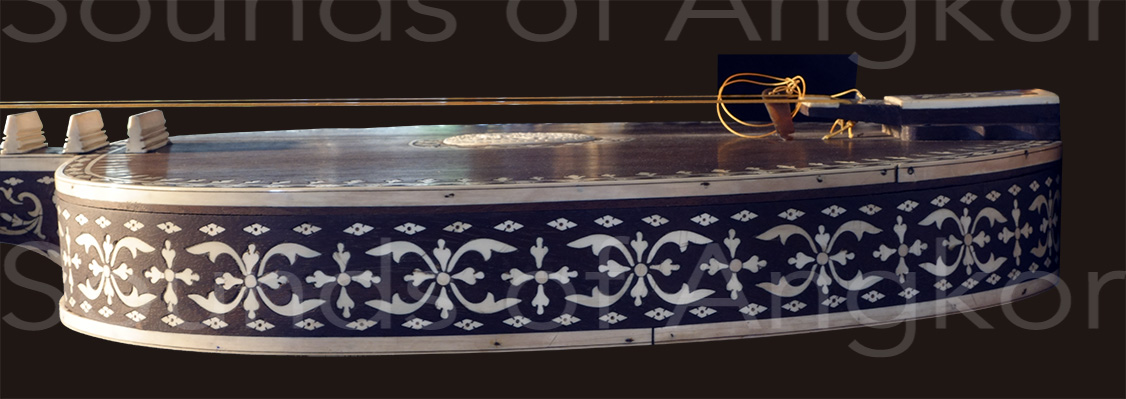

The soundbox

Organology

What distinguishes the technology of the chapei from that of the modern Western lutes is the way in which its soundbox is designed: it is monoxyle, that is to say, carved in a single piece of wood. The bottom and sides of the soundbox are of variable thickness depending on the wood species used and the manufacturers; the order of magnitude is one centimeter. In the West, the soundbox of the guitar, for example, is made with a background, a soundboard and fishplates. The thickness of the wood is reduced to a minimum in order to balance sound power, musical color and robustness. To give an idea, the thickness of the guitar's soundboard is of the order of 2.7 to 2.8 mm. However, it has reinforcements glued inside called ‘dams’. The monoxyle lutes existed in the Middle Ages in the West and are still prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa today.

The species of wood used before the Khmer Rouge revolution are beng or khnor nang (domestic fruit jackfruit).

Symbolic

The soundbox, in addition to its amplifying function, has a variable symbolic evoked by its form. The denomination of this form varies according to the musicians and the manufacturers:

- The leaf of the Bodhi tree under which Buddha Shakyamuni attained enlightenment. It symbolizes wisdom.

- The leaf of sīmā, characteristic of the carved stones delimiting the sacred space of the Buddhist temples (vihara). Symbolic: “magic” protection.

- Pineapple: trapezoid with rounded corners.

- Sapote fruit or crocodile egg: oval.

- Face of young girl muk neang, according to ethnomusicologist Jacques Brunet.

The soundboard

Organology

For the soundboard, manufacturers use roluoh wood, more rarely sâmraong. The piece of wood about one centimeter thick is glued (formerly with fish skin glue), pegged or screwed on the soundboard.

The soundboard's central decor

Organology

One to five orifices are provided in the center of the soundboard to allow air vibrating to escape the soundbox. On the chapei of the Musée de la Musique in Paris, a tiny hole (1mm) was pierced at the back of the soundbox, in the center.

Symbolic

These orifices are often five in number, arranged in the manner of the towers of the temple of Angkor Wat: a larger central opening and four smaller ones all around in square or, more rarely, five holes of the same diameter. There are also three lining holes, such as the temples dedicated to the Hindu Trimurti (Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva) or representing the Three Jewels of Buddhism (Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha).

The tailpiece

Organology

The tailpiece was formerly made of a simple piece of wood (or metal (?), “Player of chapei 1” Émile Gsell) on which were attached the strings. In the fairly recent past - which is not yet able to date precisely - the tailpiece has become more complex. A piece of wood, bone or metal has been added between the tailpiece proper and the base of the strings. Its objective was to obtain a “parasite” vibration already known on the kropeu, but also on the ancient Indian zithers; this device is visible on the high reliefs of Hindu temples in India.

The oldest known tailpiece is the one of the Chapei of the Musée de la Musique of Paris (ref E.1177). It is wooden with a central decorative groove (see slideshow below).

Symbolic

The tailpiece is a marker of the belonging of the chapei's creators-users to South-East Asia and China's culture. It is called "toad", a batrachian confused with the frog in the popular imagination. This animal is biologically and symbolically linked to water. For more than 2,000 years, it has been represented on the bronze drums of the Đông Sơn period (Vietnam). On the chapei, the toad is stylized, rarely represented as its physical reality. We must also look at the tailpiece profile to realize this relationship.

It can be explicitly zoomorphic (frog, toad, turtle) as can be seen in the images above.

The fretboard

Organology

We call “fretboard” the section of the neck between its birth in the soundbox, and the nut. Its length is variable. It is related to the size of the soundbox itself and the one of the musician (female or male). In fact, a too long fretboard may be inappropriate for a small person in size. Depending on the manufacturers, there are two ways to determine its length:

- One-and-a-half times the length of the soundbox is repeated.

- The location of the nut with the distance from the socket is first fixed at half the circumference of the soundbox. The length is obtained by a string, the length of which is equal to the circumference of the soundbox, which is then twisted in two.

The fretboard of contemporary chapei is flat to allow the mechanization of the manufacturing. But in the past, the fretboard of some instruments was slightly curved. According to the manufacturer Bora Rith, the reason could be ergonomic: a slight curvature allows the musician to wait for the top of the fretboard more readily. But it could also have a symbolic reason.

Symbolic of the neck (both fretboard and head)

The neck symbolizes the long body of the nāga-crocodile. As we said above, some old chapei's fretboards are slightly curved like the back of the crocodile. One can also see a symbolization of the bow of Ream in the Reamker.

Frets

Organology

The frets of the chapei are high. They are different from those of the guitar and Middle Eastern lutes, which, when they exist, measure only one millimeter in height. In Cambodia, another instrument shares this characteristic: the takhê (kropeu) zither. More generally, in Asia, there are high frets on most lutes. The list is too long to report them all.

But a question arises: are the high frets originating in Cambodia or elsewhere? Very clever who could answer such a question. The iconography of Khmer temples doesn't show any instrument with such frets. However, we have already hypothesized, by observing the position of the hands of some Bayon and Banteay Chhmar zither players, that their instrument was not directly related to the stick monochord zither, ancestor of contemporary ksae diev (ksae muoy). On the one hand, the position of the hands doesn't allow to play with the so-called ‘partial’ technique; on the other hand, the upper resonator is no longer placed on the chest but at the level of the shoulder or above her. This would tend to prove that there was another type of zither that would have featured frets. It is known that such zithers have existed since very ancient times in India. It is not unlikely that they would be played in Cambodia during the Angkorian era. That being said, there is no evidence that there is a link between the Angkorian zither, the takhê zither and the chapei. But it is a path of reflection and research. Let's continue our reasoning, even if we cannot prove anything yet. The fretted zither, which we have proposed a reconstruction, is fragile and not very sound. The creation of takhê as a substitute has the advantage of offering a more powerful sound. The instrument remains heavy, however. The chapei is then an in-between acceptable between sound power, acoustic interest and maneuverability. It is, moreover, both melodic and rhythmic.

The technology of high frets allows the musician to adjust the pitch of the note, enrich the aesthetics of the musical playing by modulating the frequency at will and play vibratos.

Depending on the period and the manufacturer, the frets are made of wood, bone or both, that is to say the wood stuck on the fretboard and the bone under the string. They are decreasing in height from the top of the handle. Their number is twelve or thirteen. In the nineteenth century they numbered fifteen; some of them were stuck on the soundbox. (see the photo of Émile Gsell, 19th century).

Symbolic

The frets have no symbolic link with the nāga but rather with the crocodile. Indeed, they represent its backbone as in the takhê zither which was formerly shaped like a crocodile. This representation of the crocodile instead of nāga isn't exceptional. Éveline Porée-Maspéro, in her Étude sur les rites agraires des Cambodgiens (Study of Cambodian Agrarian Rites), puts forward the idea that “‘the crocodile banner’, tong kropeu, used in various forms in most ceremonies, represented a crocodile skin. It is indeed the emblem of the Cambodian himself, since there is an intimate relationship between it (the crocodile skin) and the one who does it”. She adds: “Legends, rites, decorative techniques, thus prove the existence of old totemic beliefs in Cambodia. The current country is mainly composed of flood plains, the main totem is the nāga-crocodile”. The notion of nāga-crocodile seems to apply perfectly to the neck of the chapei.

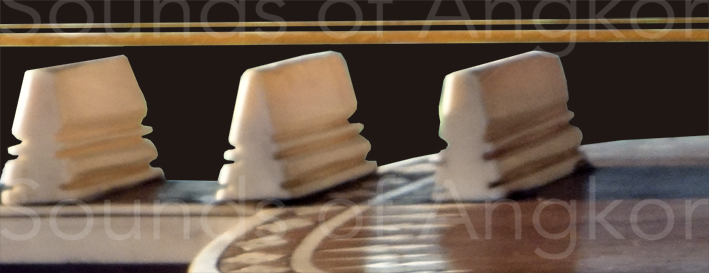

The nut

Organology

The nut is the piece of wood at the junction of the fretboard and the pegbox (both being one and the same piece). It matches the width of the handle at its base and supports the upper end of the strings before they dive to the pegbox. Its shape is variable and, as a result, it bears differentiated names in relation with its evocations. It is embedded in the fretboard thanks to a device of tenon and mortise. It is usually made of trâyoeung wood.

Symbolic

The nut often represents the goddess of the Earth, Braḥ Dharaṇī (Phra Thorani), also known as Neang Konghing in Cambodia. One might wonder why this deity is present on the chapei. To understand it, one must remember its role in the rescue of the future Buddha. The texts tell us that after going to the Bodhi tree, the Bodhisattva sat on a grassy litter offered by the peasant Sotthiya to prepare for enlightenment. This is the moment chosen by Māra - the personification of forces opposed to enlightenment - to assail him. Summoning his army, the great king took a terrible aspect and went to Gautama, who, remaining impassive, pushed him away from the ray of light coming from his forehead. Disappointed in her attempt to intimidate, Māra sent her daughters, hoping their charms would operate where the weapons had failed. They approached the Bodhisattva and unfolded in their favor ‘their magic’, but in vain.

Māra, however, didn't confess yet defeated and returned to the assault. During this new confrontation, he was distressed at the appearance of the goddess Braḥ Dharaṇī that the future Buddha took to witness, asking her to attest his rights to the seat of Awakening or ‘diamond’ throne. At the sight of this apparition, Māra's army, made up of demonic beings and monsters, fled and Māra was defeated.

As a result of this story, a very strong legend has been added in Cambodia. It says that not only did the Great Earth appear, but that the twist of Braḥ Dharaṇī's long hair still wet with water poured out by the innumerable donations and alms donated by the Bodhisattva, drowned the evil army and that, definitively defeated Māra returned to his domain.

The nut also bears other names evoking the character or animal he represents: Têp Prânâm, sva (monkey).

The pegbox

Organology

The pegbox is a integral part of the neck situated between the nut and the head. It is longitudinally pierced through to receive the pegs (2, 3 or 4). Its upper part is open to let the strings pass. It is more or less worked according to the instruments. Its upper part, around the slit in which the strings pass, is sometimes covered with a wafer carved ivory (formerly), bone or resin.

Symbolic

The pegbox represents the makara, an aquatic animal originally belonging to the mythological bestiary of India. It has an elephant's trunk, a crocodile's teeth and a fish's tail. It is considered a fertile creature linked to fertility. In Angkorian architecture, it is often found at the ends of lintels or pediments, sometimes spitting pearls, small figures or the nāga. In the case of chapei, its shape is very refined.

The pegs

Pegs are turned wood, sometimes decorated with bone parts. On the instrument of theMusée de la Musique de Paris (ref. E.1177), they are in ivory. On the instruments photographed by Émile Gsell, a metal ring (silver?) Adorned the center of the ivory pegs.

The head

Organology

The head is undoubtedly the most spectacular piece, especially on the oldest instruments. Depending on its degree of curvature, two techniques were used.

- When the curve is weak (the totality of the instruments since the Khmer rouge revolution), the head is carved without torsion.

- In the past, the head was also thinned and bandaged. So it had a certain flexibility that guaranteed its durability in front of mechanical hazards.

At all times, the size of the head varies from 10 to 70 cm with an angle of 10 to 90° facing backwards, that is to say towards the musician in playing position. This precision is useful because until the end of the 1960s, a short-handled chapei (chapei dang klei or chapei touch) existed whose head's curvature was reversed, that is to say the opposite of the musician in playing position.

The head of the ancient chapei was very often decorated with engravings, sculptures in bas-relief, the whole covered with red and / or black natural lacquer, sometimes of gilding with the stencil. (See slideshow below).

Symbolic

This head symbolizes the nāga (neak). The nāga is a mythical being both admired and feared by the Khmers. It is simultaneously a symbol of fertility, prosperity and power. Its image is reflected in the everyday life of the peasants - sickles, drawbars - and in the religious animist, Hindu and Buddhist worlds. The ornaments of the musical instruments (the head of the contemporary ksae diev monochord, the large war drums' stands and thimila drums of the Angkorian period in particular) borrow the figure of the nāga as a symbol of protection and power. Brahmanism, giving way to Buddhism, also ceded to it the worship of nāga, which became one of the protectors of Buddhism and one of the guarantors of the prosperity of the followers. The temples of Theravada Buddhism are also invested with the image of that reptile, with, among other things, nāga-shaped balustrades, roofs and candleholders.

The order of monks in Cambodia is renamed ‘nāga’ or ‘nak’, to designate the novice who will enter the orders during the ordination ceremony. This ceremony is called ‘bambuos nak’: ordination of the nāga. A legend has it that in the past, a nāga that took on a human shape was admitted among the Buddha's monk-disciples. But it resumed its original shape when it fell asleep at sunset. Surprised in this shape by one of the disciples, it was expelled from the order by the Buddha because its nonhuman condition didn't allow it to take full advantage of the teaching; however, the Buddha promised that one would keep it memory. That is why even today, we call ‘nak' the future monk, and we close the ordination ceremony with the ritual question: "Are not you a nāga? ". (source) The omnipresence of the nāga therefore has multiple justifications.

On a chapei that belonged to the royal court of Cambodia during the reign of King Sisowath Monivong (1927-1941), is carved at the root of the head (see photo below), purposely, the makara spitting nāga. This symbolism is also found in the terminal parts of the roof of the vihāra.

As we have just said, one of the most impressive features of the old chapei remains its head. It is characterized by both its length and curvature, one and the other seeming ‘excessive’ especially as they bring absolutely nothing acoustically. It could be, if we take into account the depths of human nature, the result of a competition between men as there have been so many others in the history of humanity, to whom will have the most beautiful or the most impressive instrument. But we can also have an anthropological approach. The head of the chapei represents the one of the nāga itself. In the Cambodian history, this symbol protects the entrance of temples and shrines. It should be understood that the chapei players are also singers who improvise during sung contests. But in Southeast Asia, as in many parts of the world, people recourse to black magic. The French ethnomusicologist Dana Rappoport, who studied the badong funeral songs of the Toraja of Sulawesi, reports that during sung jousting, men from different villages, cast spells on themselves. She mentions the collapse of some singers during these performances.

As part of the sung jousting, there are two ways to ‘fight’ his opponent: either by being smarter in the use of ideas and the organization of words, or by casting spells. Thus, the long nāga-shaped head could have been, originally, a tool of magic protection. What other reason could have led to accept such manufacturing, transportation and handling constraints?

The strings

Organology

In Cambodia, the number of strings commonly used by musicians is now reduced to two, whereas in the past it was four, tuned two by two in unison and the fourth or fifth between them. However, we found on the Internet a musician from Takhmao named Tet Thöne, who was 78 years old in 2010. He was himself a chapei maker and had been playing since 1947. Below are three videos about him.

The strings are now made of single-strand nylon. Traditionally, the two upper strings, accompanying, were bigger than the lower ones, melodic. Sometimes the accompanying strings were made of metal. According to Keo Narom, some chapei have had in the past only one accompanying string and two melodic ones.

Before the introduction of nylon strings, mainly used by fishermen, the strings were twisted silk threads. Recall that Cambodia is a silk producer at least since the Angkorian period. This fact was reported by the Chinese chronicler Tcheou-Ta-Kouan in his text of 1296. Perhaps we also used gut strings, but for now we keep it as hypothesis. Our present research may help to confirm or refute it.

Silk is a well-known component for chordophones in Southeast Asia and China. China, Thailand and Vietnam have started again, in recent years, to use a such material.

A third string, the central one, is not playing string but a link passing through the frets to avoid losing them. We have devoted a chapter and a documentary film on this subject: The lesson of the three strings.

The plectrum

The strings of the chapei are plucked with a plectrum. This playing technique is typical of long-neck lutes in the Middle East. Traditionally, Cambodian musicians use a plectrum a few centimeters long in minced buffalo horn. But the new generation prefer a plectrum in nylon braiding created by Pich Sarath in 2010.

The plectrum is called krachak in Khmer, literally nail. Some musicians attach it to the tailpiece with a string so as not to lose it.

Proportions

In Cambodia, the size of traditional musical instruments is sometimes related to the size of the maker himself or to the one of the stallion's designer. There is also a dimensional relationship between the various parts. It is very likely that the so-called equiheptatonic scale used by the Khmers was born from the manufacture of a flute with equidistant holes or bamboo Pan flutes. The French ethnomusicologist Jacques Brunet reports how a manufacturer met by him in the 1960s operated to determine the dimensions of the fretboard: “To size the fretboard, we first fix the location of the prakiên nut whose distance to the resonance table equals half of the circumference of this box (the measurement is obtained by means of a string whose length is equal to the circumference of the soundbox, string which is then folded in two). All that remains is to reserve a place for the prânuot pegs and then carve the ornamental end of the neck which can be from 10 to 70 cm (...) ”

The chapei, a multicultural object

The chapei is integrative, like the state religion, Theravada Buddhism. It unites cultural elements of the animist Khmer fund — the crocodile, animal symbolizing of longevity like the turtle, of fertility such as the frog or the toad— and Brahmanic. However, the cultural contributions are not limited to the cultural and religious mixtures of the Khmers, they are also at the crossroads of geographical influences areas, both near and far:

- China has probably brought the flat-bottomed and ovoid-shaped soundbox.

- The countries crossed by the Silk Road have contributed to the development of the long neck, present in both China, Central Asia and the Middle East. Unless it is the opposite!

- India brought nāga and makara, taken over and staged by the Khmers.

- Thailand is the co-author of krajappi / chapei, knowing that cultural influences with Cambodia have never stopped since the fall of Angkor in the 15th century. We think, however, that the Khmer version could come from Thailand for two reasons. First, the krajappi is more complex because it has four strings and the head is more elaborate. Secondly, the term chapei would be a simplified and popular form of krajappi. This is a trend in all languages of the world, to shorten words. The opposite is more rare.

- France, during the period of the French Protectorate (1863-1953), has singularly modified the perception of the traditional musical scale of the Khmers. This auditory ‘conflict’ has increased with the advent of radio, television and now smartphones. The Khmer musical scale is called equiheptatonic (theoretical vision). It consists of seven sounds but differs from the western diatonic scale. This drift is also noticeable on fixed note instruments such as roneat xylophones, kong vong gong chimes, and khim struck string zither. The frets of the old chapei were fixed on the neck with vegetable glue or resin which allowed to reposition them according to the cultural earing of each musician. Today the position of the frets is fixed, which has the disadvantage of changing the scale in relative value when the tonic changes. There is no standard for the agreement. For example, the younger generation of the Chapei Community uses as basic: C. On the other hand, Master Kong Nai gives his instrument in D. On the other hand, the tuning of the chapei and the song of the singers are more and more aligned with the western diatonic model. This trend is amplified by the use of diatonic and chromatic electronic tuners.

- The Khmers combined the nāga and the crocodile, and created a specific symbolic universe.

Magic protection of chapei players

“Magic” is part of the daily life of the Khmer. Their spiritual universe is populated by invisible, good, harmful or ambiguous entities.

Magic practices in Cambodia

The dominant religion is Theravāda Buddhism, a religion-philosophy that bears its name because the literal translation is: Doctrine of the Ancients. If the term “Ancients” refers to the followers of early Buddhism, it takes a completely different face in Cambodia because it has integrated the epic Reamker (Khmer version of Indian Rāmāyaṇa) and also local animist beliefs. To live in harmony with all spiritual entities, the Khmers have developed individual and collective rituals celebrated daily or according to a calendar known to the community.

These practices that some will call “magical” are actually communication protocols with the spirituel entities. Some of these protocols are accessible to all, others reserved for initiates (ascetics, mediums, healers, monks ...). Communication is done using the five senses (or more depending on culture) common to humans and spiritual entities.

Artists in general, and musicians in particular, have developed their own protocols, more or less sumptuous depending on the occasion. In the traditional orchestra, there is always a person responsible for conducting the ritual (sampeah kru) preceding any performance.

The solitary musician, like the chapei player in a chlaoy chlang singing contest, finds himself in a precarious situation, whatever his experience and charisma. Considering what has just been described, the question arises: do chapei players use magic in their practice?

Magic protections

The Khmers, for the most part, have for centuries used magical protection objects, prayers and tattoos for which there are as many reasons as there are supposed dangers.

Chapei players do not escape the rule. In chlaoy chlang singing, they are more vulnerable than ever. Chlaoy chlang is a ritualized intellectual battle between two or more protagonists in which the musician is exposed in public, with his strengths and weaknesses.

A musician of the new generation met in 2019, carries permanently in his bag a krama (piece of checkered cotton) in which is carefully wrapped a tiger mustache offered by a Buddhist monk. Recall here, as we said above, that Cambodian Theravāda Buddhism is integrative. Magical practices, for curative and protective purposes, are part of the protocol arsenal of the monks.

This tiger mustache, to take only this example so characteristic, can be seen as a defensive tool, but it can also be considered as an offensive weapon; reality probably combines both uses simultaneously.

The chapei, a weapon?

The chapei, when played in chlaoy chlang singing, can be considered as a weapon because it is the main tool of this “intellectual fight” in which the protagonists compete, supported in an underlying way by a audience “pro”, “anti” or “ambiguous”, like spiritual entities. The organological and symbolic complexity of the chapei, compared to comparable elements in the Khmer culture, makes it a weapon both defensive and offensive. We will now detail these different components. In order to avoid repetition, we invite the reader to refer to the comments on the various organological components developed above:

- The symbolic animals (nāga, makara, crocodile) that enter the composition of the chapei are both offensive and defensive.

- The soundbox placed against the belly of the musician conceals both the hara and the solar plexus respectively centers of strength and emotions that the musician must protect from the eyes and magical attacks.

- At the center of the soundboard, the five central orifices - representing the five towers of the Angkor Wat temple - or a lotus flower are also symbols of protection. Remember that the five towers are surrounded by several walls and a moat.

- Formerly, the fretboard was slightly curved. Should we see a symbolization of the Ream arc in the Reamker?

- The nut is often in the image of the goddess Braḥ Dharaṇī; this mythological figure constitutes, in the wake of the three-headed nāga, another magical protection for the chapei player.

- In a more general way, the chapei, as the Hindu temple or Buddhist monastery, is also a place of symbolic withdrawal in the sense that it allows the musician, at the end of the expression of an idea, to prepare the next one by playing automatically. During this time of thinking, the kinesthetic memory takes over the intellect then free to prepare the continuation of the response.

The chapei, an aquatic and terrestrial instrument

Why the chapei is an aquatic and terrestrial instrument? In Khmer, the name “country”, in the sense of “territory”, translates as “water-land” ទឹកដី, a concept bringing to life. Formerly, before the arrival of the Brahmans, the totem of the Khmers of the plain was the crocodile. At the time of the Hinduization (from the first century CE) the nāga replaced it. The Khmers of the plain are opposed to the ones of the high regions; their totem is the kite (raptor of the Accipitridae family). Itself was replaced by the Garuda. Several of the organological components of the chapei refer to aquatic animals or deities:

- The neck refers to both crocodile and nāga's body, guardians of earth and water.

- The head represents that of the polycephalic nāga (at least three stylized heads).

- The tailpiece is called toad or frog; in profile, we guess indeed a batrachian sometimes explicitly zoomorphic.

- The soundbox was originally shaped like a turtle shell, an animal whose Sanskrit name is at the origin of the term chapei.

- The nut often represents the Princess Braḥ Dharaṇī (Phrea Thorani) who saved the Buddha by drowning the evil army of Māra thanks to the water contained in her hair.

Symbolically, the chapei is in the filiation of the kse diev zither, with its body and head of nāga; it is also in symbolic filiation with the kropeu zither (Khmer term) or takhê (Thai term) symbolizing the crocodile. These three instruments (chapei, kse diev, kropeu) have a strong aquatic symbolism.

A question arises however: we have developed in the section The mahori ensemble of Ayutthaya a theory according to which the chapei played the role of second cordophone in place of the Angkorian harp. But the harp is linked to the bird and Garuda! Here we discover a shifting paradigm between the symbolism of the Angkorian Royal Court and that of Ayutthaya.

Perhaps this is reason to think that the chapei was invented by the Thais during the Ayutthaya period, taking the lead role in relation to the saw sam sai fiddle. On the symbolic level, the Angkorian Khmers could never have offered to the chapei the role of second instrument alongside the kse diev, also an aquatic instrument! Angkorian orchestras always contain an aquatic instrument (monochord zither) and an aerial one (harp).

Le chapei, an ambiguous instrument

On the symbolic level, one could also say that chapei is an ambiguous instrument. The Khmer recognize three types of spiritual entities: auspicious, maleficent and ambiguous, like Men themselves! The animals, real or mythical (crocodile, nāga, turtle) in symbolic relation with the chapei, live both on / underground and in the waters.

The crocodile, a symbol of death, has long been feared in the real world until its virtual extinction during the Khmer Rouge revolution. It was for two reasons: its intrinsic danger and its belonging to the double aquatic and terrestrial habitat. But it is also the protector of the community, the guardian of the territory, able to punish the troublemakers of the community's order and ethics.

The nāga is both a real animal embodied by the fearsome Royal Cobra and a mythological entity. As an entity, it is worshiped for its protective virtues in Hindu temples and Buddhist monasteries (among others) but also dreaded because lurking at the bottom of the earth and the waters of which it is the guardian.

The turtle, too, shares the dual aquatic and terrestrial habitat, although it is not feared.

The chapei thus possesses, by its symbolic inheritance, this potential of ambiguities.

The chapei player, like his instrument

We have just seen that the chapei was ambiguous. But what about the musician himself?

We know that the crocodile was once the totem of the Khmers of the plain. According to the belief, young people who are not yet socialized sometimes exhibit dangerous behaviors that suggest that they have turned into crocodiles. As part of chlaoy chlang singing, the chapei player is both a musician and a singer. When he plays his instrument without singing, the "musician character" makes his procedural memory work; but at the same time, the "character-singer" activates his semantic memory to prepare speech or riposte. In preparing its response, the whole "character" becomes ambiguous because no one can imagine what will happen: the riposte will it be "flattering", "killer" or "ambiguous"?

See also:

The “Lesson of the three strings”

The arak ensemble of the Wat Reach Bo

The chapei players, by Émile Gsell

The chapei of the Musée de la Musique of Paris

Edited by Cambodian Living Arts, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

© Cambodian Living Arts 2018-2023, © Patrick Kersalé 1998-2024