The chapei players, by Émile Gsell

Texts, photos, videos: © Patrick Kersalé 1998-2019, except special mention.

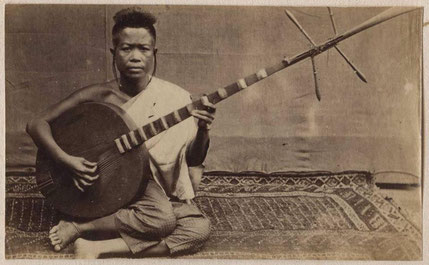

In the career of a researcher, there are sometimes beautiful stories, even miracles! A few years ago, I discovered on the Internet the sepia-colored photograph of a chapei female player from the Royal Palace of Cambodia taken by the French photographer Émile Gsell circa 1866-1870 (here referred to as “chapei 1 player”).

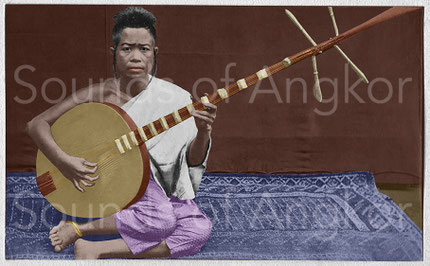

I discovered later a second picture from Émile Gsell on which we can see another player of chapei, in the same position and with an instrument very close to the previous one (denominated here: “player of chapei 2”).

About Émile Gsell

Émile Gsell was born in Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, Haut-Rhin, France on 31 December 1838. He served in the military from 1858 to 1866, during which time he learned photography and travelled to Cochin China (now Southern Vietnam).

In Cochin China, Gsell was hired by the Commission d'exploration du Mékong, directed by Ernest Doudart de Lagrée (1823 - 1868), to photograph the ruins of Angkor. Gsell accompanied the expedition to Cambodia and Siam (now Thailand, and at the time in possession of Angkor) from June to September or October 1866, often receiving suggestions for photographic points of view from Doudart de Lagrée.

Also in 1866, following the expedition, Gsell established himself as a commercial photographer in Saigon, becoming the first professional photographer to do so in that city.

In the first half of 1873 Gsell returned to Angkor and travelled through Cambodia with Louis Delaporte. On the strength of his Cambodian photographs Gsell was awarded a medal of merit at the Vienna International Exhibition, which was held from 1 May to the 31 October 1873 and during which Gsell exhibited two albums of photographs, one of the ruins of Angkor and the other of "the mores, customs, and types of the Annamite and Cambodian populations".

In April 1875, Gsell accompanied a mission, led by Brossard de Corbigny, to Huế, though he was not allowed to photograph the people he met nor the Citadel. However, two of his photographs demonstrate that he was in Hanoi at the end of 1875 and from November 1876 to January 1877 Gsell was able to take many views of Tonkin (now Northern Vietnam).

Émile Gsell died at home in Saigon on 16 October 1879.

Meeting with a descendant of Émile Gsell

While on a mission to Luang Prabang (Laos), I stayed in one of the many guesthouses in the city, run by a Vietnamese family from Hanoi. In the lobby of the establishment, in front of me, a Frenchman married to a Vietnamese. The conversation began when he suddenly said to me:

- I have a Jewish name but I'm not Jewish ...

- What is your name? I asked him.

- Gsell, Frédéric Gsell.

This name, whose French pronunciation I first discovered, echoed in me. The only time I heard it was from an Australian, Nick Coffill, at his lectures on the history of photography in Cambodia at Bambu Stage (Siem Reap). He pronounced "djezel". However, I instantly made the connection since I was working the same day on the photograph of Emile Gsell. I asked him then:

- Are you related to Émile Gsell, the 19th century photographer?

- Yes, he is my great-great-grandfather. He was born in Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines ...

No doubt, by this instantaneous detail, that he spoke true.

There was a chance in a thousand billion to meet this guy at this moment. Would it be a remote control of Émile since the afterlife? The more time passes and the more I think it. This meeting might not be fortuitous ...

Then began a relationship with the idea of paying tribute to his grandfather, in his native village (perhaps a choice of Émile himself, would he have had a strong ego?)

Colorization of Émile Gsell's photographs

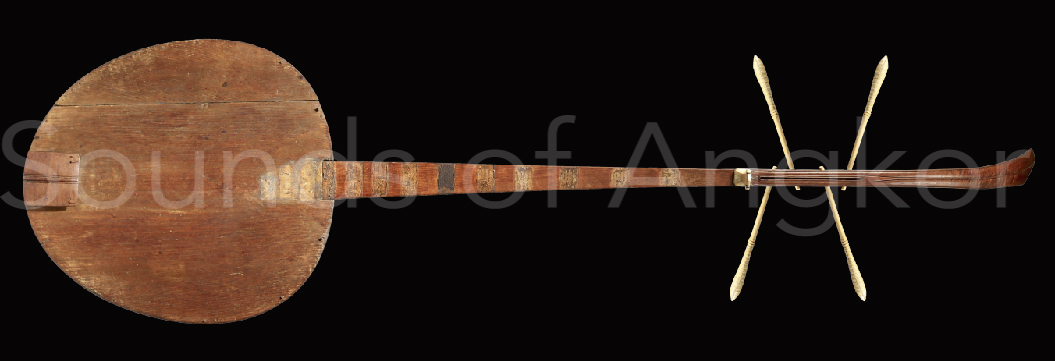

At the end of March 2018, I discovered that the “player of chapei 1” had been colorized by the Cambodian company of drinking water VITAL. The image was attractive but the colorization did not highlight the components of the instrument. So, I decided, on April 1, 2018, to make my own organological colorization. However, I missed a few things about the materials. Miraculously I discovered the same day that the Musée de la Musique of Paris had a chapei (ref. E.1177) highlighted thanks to new photographs signed Claude Germain. By studying these images, I discover that this instrument is similar to those photographed by Émile Gsell. The organs are identical. The remaining peg is made of ivory.

The instrument was acquired on December 25, 1887, eight years after the death of Émile Gsell. It can therefore be said that this instrument dates from the period during which the latter realized his shots.

We will now confront the organological details of the instrument with the images of Émile Gsell.

The first observation we can make is that the instrument of the Musée de la Musique of Paris is very close to those photographed by Émile Gsell. We could almost say that these three instruments come out of the same workshop. However, we don't have the means to prove it because at this time, and since the end of the 18th century if we cross the Cambodian and Thai iconographic sources, there is a certain shape's standardization. This is still the case today with the few Cambodian manufacturers of the beginning of the 21st century. Indeed, they respond to a specific request from the musicians and don't have the economic choice to propose something else. Even if the individualities, sometimes strong in the world of the chapei, express themselves singularly, there is a certain standardization of the sound of the instruments, with however differences seen from the side of the specialists. At first glance, these three chapei of the late 19th century are structurally and aesthetically very different from those of the 2010's.

The sound box has the shape of the sapote fruit; however, another interpretation is that it is the shape of the leaf of the Bodhi tree.

The shape of the end parts are very close. The value of the curve doesn't appear on these images taken from the front. However, we will see later, on a third shot of Émile Gsell, that it is similar. In the image of chapei 1 we clearly notice the central groove.

The pegs of the three instruments are thin and slender. Those of chapei 1 are whitish (ivory) with a ring in the middle. Those of the chapei 2 seem to be in wood but it is difficult to affirm because of the poor quality of the original image; however, if we compare their hue to that of the frets, they are darker. We find on the dowels of the two instruments of the image of the chapei 2 a protuberance in the middle, realized during the turning.

On the 18th and 19th centuries, the iconography clearly shows frets stuck on the soundboard, like many ancient and contemporary Asian lutes.

On the chapei 1, a fret is glued to the edge of the neck and the soundboard and five others in gradient on the table.

On the chapei 2, a fret is glued to the edge of the neck and two frets equal length on the soundboard.

The tailpiece of chapei 2 is aesthetically identical to that of the instrument of the Musée de la Musique of Paris. We will notice the two central grooves. Note that at this time, there is no ‘noisemaker’ on the tailpieces, like the Indian lute and lute or Khmer kropeu.

On the other hand, a ‘noisemaker’ device appears to exist inside the sound box. Indeed, the fact sheet of the Musée de la Musique mentions "3 springs mounted around a metal rod (noisemakers?)". It could be one of the best-kept secrets of the old chapei factors mentioned by Master Sok Duch recently disappeared. For our part, we recently discovered at a drum manufacturer that springs were also used inside the big pagoda drums.

The tailpiece of chapei 1 is light in color.

We can appreciate here the end part of the chapei ref. E.1177 on the two photographs of Claude Germain (Musée de la Musique, Philharmonie de Paris).

The mahori ensemble of King Norodom

This photograph of Émile Gsell shows female musicians of King Norodom's mahori (mohori) ensemble (c. 1866-1870). The player of chapei is none other than the character of the photo ‘chapei player 1’. The neck of the chapei appears at a different angle, allowing to appreciate its length. However, we don't pronounce on the value the angle of the curve because the perspective effects on this part of the instrument are misleading. We have also pointed out in another article on this site that Cambodian painters have not totally solved the question of the perspective of the head of chapei; it seems that photography offers us optical illusions as well!

In this image, we find that at least two instruments are typically Thai: the goblet drum (far left) and the spike fiddle in the center. The comparison with instruments preserved in Thailand (Bangkok National Museum and Suan Pakkad Palace Museum) attests to this.

It is known that King Norodom (originally named Ang Voddey), the eldest son of King Ang Duong, spent his youth studying in Bangkok, to strengthen ties between the Khmer Kingdom and Siam, which at that time still exercised his suzerainty on Cambodia. So, this ruler spoke Khmer and Thai. No wonder then that all or some of the instruments of his court could be Thai. This raises the question of their name within the court: Thai or Khmer? In the section “The chapei of the Musée de la Musique of Paris” you will find information on the probable origin of the chapei.

Let us mention these two options (instruments from left to right):

| Organological denomination | Thai name | Khmer name |

| Goblet drum | thon (โทน) |

skor thon (ស្គរថូន) |

| Xylophone (soprano) | ranat ek (ระนาดเอก) | roneat ek (រនាតឯក) |

| Small cymbals | ching (ฉิ่ง) | chhing (ឈិង) |

| Blade metallophone (soprano ?) | ranat ek lek (ระนาดเอกเหล็ก) | roneat dek (រនាតដែក) |

| Trichord spike fiddle | saw sam sai (ซอสามสาย) | tro khmer (ទ្រខ្មែរ) |

| Circular gong chime (ténor) | khong wong yai (ฆ้องวงใหญ่) | kong vong thom (គងវង់ធំ) |

| Long neck lute | krajappi, grajabpi (กระจับปี่) | chapei (ចាប៉ី) |

| Board zither | jakhe (จะเข้) |

krapeu (ក្រពើ), takhe (តាខេ) |

| Flute | khlui (ขลุ่ย) | khloy (ខ្លុយ) |

| Frame drum | rammana (รำมะนา) | skor romonea (ស្គររមនា) |

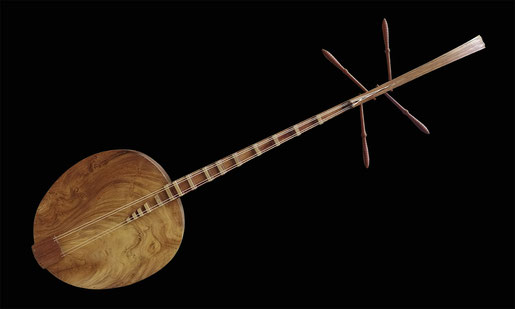

Reconstruction of the chapei from the Émile Gsell's photography

2012. We discovered on the Internet the photography of Émile Gsell's chapei. This image, taken between 1866 and 1870, was fascinating and the instrument played by this musician from the royal palace is no less so. Then began to germinate the dream of a reconstruction. But a lot of data was unknown to us. It was then that a meticulous investigation, interspersed with beautiful meetings and incredible synchronicities, will lead us to the final result.

2016. We contacted the luthier of the royal court of Thailand close to the Myanmar border, but unfortunately without success because too far to follow such a project from Cambodia.

December 2018. “Synchronic” meeting in Luang Prabang (Laos) of Frédéric Gsell, descendant of the photographer Émile Gsell.

April 2019. The discovery of the existence of the chapei of the Musée de Paris thanks to Frédéric Gsell, was going to modify our initial project. Our meeting with Nattapann Nuch-ampann (ณั ฐ พันธุ์ นุช อำ พันธ์) also facilitated the reconstruction process, and our visit to the Suan Pakkad Museum in Bangkok was decisive.

July 9, 2019. We take readings of the instrument in the reserves of the Musée de la Musique de Paris.

October 27, 2019. We gave the plan, the dimensions and the photographs to Leng Pohy, our sculptor partner in Siem Reap then decided to build two chapei simultaneously, the second allowing to correct the errors of the first one. We had to deviate from the purist path of an identical reconstruction for ecological and legal reasons by using substitute materials. The soundbox and the neck of the original chapei were made of beng wood: Afzelia xylocarpa, Craib. We replaced it with thnong (Pterocarpus macrocarpus, L.). The soundboard was in roluoh (Erythrina orientalis, L.), we replaced it with the same essence as the body. Originally, the tuning pegs and the nut were made of elephant ivory, available in abundance in the 19th century; we replaced them with kranhung wood: (Dalbergia cochinchinensis, Pierre). The frets of the original instrument have disappeared, but it appears, according to research at the Suan Pakkad Palace Museum in Bangkok, that they were made of wood and topped with bamboo. In the absence of any other tangible source, we decided to follow this path.

The first delicate operation was to bandage the head. Leng Pohy once built oxcarts for which he learned to do this. For the original instrument of the Musée de la Musique de Paris, our expertise demonstrated that the head had been bandaged and that this resulted in a slight deviation of the axis of the head from the neck. The wood had warped. In our experience, the same phenomenon has occurred, however to a lesser extent. For this reconstruction, we decided to use modern tools (band and circular saws, drill, sander). Two experienced sculptors contributed for the pegbox, the neck and the tailpiece. The most delicate operation was the piercing of the pegbox for the insertion of the four pegs, because they had to be both parallel in pairs and on the same plane. Three people were required to maintain the instrument and control the two drilling axes.

Philippe Brousseau,

founder of Jayav'Art in Siem Reap, made the medallion on the back of the chapei's soundbox. The original drawing was transferred by decal onto a wooden board coated with gesso and covered with lacquer.

February 24, 2020. The second chapei is officially finished. Thus, between the discovery by ourselves of the photography of Emile Gsell's chapei in 2012 and the final reconstruction, seven years have passed. We have learned a lot from this experience.

See also ...

The “Lesson of the three strings”

The arak ensemble of the Wat Reach Bo

The chapei of the Musée de la Musique of Paris

Edited by Cambodian Living Arts, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

© Cambodian Living Arts 2018-2023, © Patrick Kersalé 1998-2023