The Thai krajappi

Texts, photos, videos: © Patrick Kersalé 1998-2023, except special mention.

Although UNESCO has classified the only Khmer instrument named Chapei Dang Veng, the study of its history and organology cannot escape an investigation to the Thai krajappi's* world whose form and technology are similar. Three essential reasons motivate this choice:

- The Kingdom of Cambodia has long lived under the rule of the Kingdom of Siam, and three of its current provinces have long belonged to it: Siem Reap, Sisophon and Battambang. For more information, click here.

- The oldest Chapei Dang Veng's iconography is known to us thanks to the pictures of French photographer Émile Gsell; they demonstrate a common technology, in detail, with two krajappi belonging to the Suan Pakkad Palace Museum in Bangkok.

- The Thai-Khmer community in the Buriram, Surin and Sisaket's provinces uses the name ‘krajappi’ to describe what the Khmer of Cambodia would call chapei. Click here for an example.

* Given the recurrence of the krajappi word as the main theme, we don't use italics, as for chapei.

Old iconography of krajappi in Thailand

One of the oldest representation of krajappi in Thailand seems to date from the eighteenth century. The picture is an Ayutthaya School's painting, owned by Jim Thompson's house in Bangkok. It is from the book about Jim Thompson's house. It represents Prince Siddhartha leaving at night the palace where he grew up.

In the current state of our research, this representation of krajappi would be the oldest one. It is a mahori orchestra, a music practiced in the Ayutthaya court at least since the mid-eighteenth century, but certainly older. We can already see the structure of Khmer orchestras phleng arak boran and phleng kar boran, that is to say by transposing the names of Khmer instruments: the chapei lute, the tro Khmer fiddle, the pei ar oboe with its large reed, the goblet drums skor arak or skor daey and a skor romonea frame drum seen from the front. While this last drum is not present in the phleng arak boran and phleng kar boran, the structure of the musical ensemble is similar. We know that traditional Cambodian orchestras were, and remain, geometrically variable according to the provinces, the formations themselves, the availability of musicians and instruments.

For the Thai instruments names, see the following chapter: The Buddhaisawan Chapel (Bangkok).

We have retained the French version (reworked) of the monk Dhamma Sāmi in his book “The life of Buddha and his main disciples” to describe the scene depicted here; it is recurrent in the pagodas of Theravada Buddhism.

“Returning to the palace, on this Monday of the full moon of July 97 according to the calendar of the Great Era, Prince Siddhartha headed straight for the main living room, without bothering to climb into the room where the princess was sitting and his baby. Once there, he lay down on his vast throne, sheltered by a large white parasol. All around him, young and beautiful women danced, others played musical instruments, others sang pleasant melodies, all richly dressed, carefully coiffed and pleasantly scented. Unlike the previous days, the prince no longer felt the slightest pleasure at these festivities. The kilesā (mental impurities) weighed on him now as long as he no longer accepted to undergo them, however tiny they may be. That evening, insensitive to the graceful spectacle of the dancers, to the delicate harmonies of the musicians and to the sweetness of the melody of the singers, he fell asleep.

Seeing the sleeping prince, the women of the palace, embarrassed, dared no movement, for fear of disturbing him in his sleep. They did not venture to leave, the order was not given to them. All remained on the spot. As the hour progressed, they fell asleep on the spot in a total disorder: the scattered bodies were directed in all directions, tongues hung, some snored, drooled, groaned, talked while sleeping, chewed, some had their mouths wide open, d others were half naked in the unconsciousness of sleep. After the middle of the night, the prince awoke. Contemplating the distressing spectacle that presented itself to him, he was finally satiated with kilesā. Disgusted, disgusted by this disgusting vision that made him think of a messy mass grave where corpses pile up pell-mell, he depressed. A thought crossed his mind: ‘And to say that I remained carefree, immersed in this world of sensory pleasures twenty-eight years!’

It is at this moment that the prince decides to put immediately at work his decision to leave the palace for the forest ...”

In almost all cases, the female musicians are represented asleep, as described in the original text. However, here, the princess and her baby are immersed in sleep while the musicians play for awake spectators.

As is often the case for the illustration of mythological or historical texts, artists represent the musical instruments of their immediate environment, but not those of the time they illustrate. So do not see there, or anywhere else, the musical instruments of the time of the Buddha.

The Buddhaisawan Chapel (Bangkok)

The Buddhaisawan Chapel in Bangkok was built in 1795 to house the statue of the Lion Buddha (Phra Puttha Sihing) of Sinhalese origin dating back to the 15th century. It is located inside the Bangkok National Museum. This chapel is now consecrated as a Buddhist temple and many worshipers frequent it daily, but no monk is attached to it. It contains the illustration of the 548th and last life of the Buddha in 28 murals made between 1795 and 1797.

The state of conservation of the panels is uneven and the paintings have been restored several times. The same panel can represent various events, sometimes anachronistic, separated by plant motifs (trees, bushes), minerals (rocks) or aquatic (ponds, rivers, seas). Important events are always painted on a red background and topped with zigzag decorations, typically Siamese.

The painting was made by the method called tempera, on walls washed and dried; the natural colors were applied on the dry walls, then stabilized with natural fixatives.

We present here the completeness of the panels of this chapel containing at least one krajappi lute as they are beautiful and representative of the Buddhist culture of that time. The krajappi are all played by women and, in a unique case, by a mythological being.

These paintings date from the beginning of the Rattanakosin period (1782-1932) of King Rama I, that's to say just from the end of the Ayutthaya Kingdom (1350-1767). They combine illustrating elements of the Buddha's life, from His birth to His awakening, and scenes from the court life. They are a precious testimony of Ayutthaya's life as they show the various ensembles and instruments played during the ceremonies. However, it's important to weigh this point of view that we are developing here. All these ensembles belong to the mahori musical style and all instruments are still part of the contemporary Thai musical heritage: saw sam sai (ซอสามสาย) fiddle, krajappi (กระจับปี่) lute, khlui (ขลุ่ย) flute, klong thap (กลอง ทับ) or thon/rammana drums (โทนรำมะนา), ching (ฉิ่ง) small cymbals, krap phuang blade percussion (กรับพวง). These instruments, with the exception of the krap phuang, also belong to the Khmer instrumental heritage in slightly different forms.

We will, however, focus here on the only krajappi.

The visit to Tavatimsa heaven

“For three months during the rainy season, the Buddha preached to his mother and the gods, including ruler of Tavatimsa heaven, the god Indra. On his way to Tavatimsa heaven, the Buddha passes above the head of an evil serpent or Naga in human and princely form. Enraged, and assuming his serpent form, the evil Naga battles with another naga, Mogellana, who is a disciple of the Buddha, but to go/to avail, until Mogellana assumes the guise of a Garuda, the half bird half man enemy of the nagas the double miracle at Sravasti. To convince dissenters, the Buddha performs miracles in which a fully laden mango tree springs from a seed, and the Buddha himself appears in multiple forms simultaneously: as single walking figure, two seated figures and two reclining figures platforms erected by the dissenters on which to perform rival magic are destroyed by a storm caused by the green god Indra.”

The krajappi shown here has an oval soundbox and three pegs. The frets are not visible.

The death and cremation of King Suddhodana

“The Buddha’s father, King Suddhodana, sends the ninth emissary to find the Buddha to return to Kapilavastu, to preach to his father and relatives."

Two orchestras are mirrored on both sides of the cremation tower. The krajappi frets are not visible. The two resonance boxes have substantially different shapes; the one on the left is closer to the shape of the leaf of the Bodhi tree. The one on the right shows four tuning pegs.

The Buddha descends the triple staircase

“From Tavatimsa heaven down to the world of men, accompanied by the god Indra, the Brahma and celestial musicians, the Buddha descends the triple staircase of gold, silver and glittering jewels. At the time of the descent, a miracle enables the three worlds, of the heavens, earth and the hells, to be simultaneously visible to each other. After his descent to earth, the Buddha preaches to assembled followers.”

On this scene, two krajappi are represented in two different contexts. In the upper left, Gandharva Pañcaśikha plays krajappi. He holds in his other two hands two small rattle drums, one of the attributes of God Shiva when he is represented as the God of Dance. Indra who holds the sword and the conch accompany him. The soundbox of his krajappi is oval. The instrument has five tuning pegs but only three strings. Perhaps we should see there a symbolic representation: the five pegs could represent the five mountains of the Meru or remain the gods of Hinduism and the three strings, the three gods of Trimurti: Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva.

The second krajappi is located under the stairway through which the Buddha descends into the world of humans. The instrument has four strings and the frets are visible. The musicians have the same hairstyle as the chapei player of the Royal Palace of Phnom Penh photographed by Émile Gsell at the same time. It is clear from this detail that the Siam Court in Bangkok and the Cambodia Court in Phnom Penh are close in culture.

Death, cremation and entry into Nirvana of Princess Yasodhara

"Princess Yasodhara is the wife of the Buddha whom he abandoned at the same time as his son when he left the palace one night. Legend has it that King Udena had three spouses; two of them, Mâgandiyâ and Sâmâvatî, were fierce rivals: one was a disciple of the Buddha, the other was jealous and vindictive. While the Buddha was visiting the kingdom, each queen behaved accordingly: the first received him with food offerings, the second spread rumors and barked the dogs after him. "

It is also a lute in this story: "At that time, the king used to share his time equally between his three women, spending seven days in turn in the apartment of each of them. Magandyia, knowing that he would go the next day or two days later to Samavati's apartment, sent word to his uncle: ‘Send me a serpent, whose fangs you have soaked with it.’ This was done. The king had custom, wherever he went, to carry his magical lute, elephant charmer. In the soundboard of the instrument, there was a hole. Mâgandiyâ then introduced the snake and blocked the opening with a bouquet of flowers. For two or three days, the snake remained in the lute ...” Read more here.

The krajappi depicted here has a soundbox whose shape is close to that of the leaf of the Bodhi tree. Twenty frets on the neck and six on the soundboard. Only two pegs are visible.

Death, cremation and entry into Nirvana of Princess Yasodhara

"Princess Yasodhara is the wife of the Buddha whom he abandoned at the same time as his son when he left the palace one night. Legend has it that King Udena had three spouses; two of them, Mâgandiyâ and Sâmâvatî, were fierce rivals: one was a disciple of the Buddha, the other was jealous and vindictive. While the Buddha was visiting the kingdom, each queen behaved accordingly: the first received him with food offerings, the second spread rumors and barked the dogs after him. "

It is also a lute in this story: "At that time, the king used to share his time equally between his three women, spending seven days in turn in the apartment of each of them. Magandyia, knowing that he would go the next day or two days later to Samavati's apartment, sent word to his uncle: ‘Send me a serpent, whose fangs you have soaked with it.’ This was done. The king had custom, wherever he went, to carry his magical lute, elephant charmer. In the soundboard of the instrument, there was a hole. Mâgandiyâ then introduced the snake and blocked the opening with a bouquet of flowers. For two or three days, the snake remained in the lute ...” Read more here.

The krajappi depicted here has a soundbox whose shape is close to that of the leaf of the Bodhi tree. Twenty frets on the neck and six on the soundboard. Only two pegs are visible.

Engagement gift receiving, procession and celebration of royal wedding …

“This scene depicts the engagement, the procession and the celebration of the royal wedding of the Bodhisattva's parents, the Suddhodana King of the Sakya clan and Princess Maha Maya at the Kapilavastu Palace. The future couple, surrounded by members of the Court, face each other: between them is a bai sri (floral arrangement). On the left, Prince Suddhodana Gautama is flanked by Brahma with four faces and Indra with green. On the right are Princess Maha Maya and her suite.”

The orchestra is composed of six instruments. From left to right: small cymbals, fiddle, krajappi lute, frame drum, goblet drum and a percussion instrument made of a bundle of hardwood and brass slats, tied together at one end called krap phuang (กรับพวง). The two drum players have their mouths ajar, which means they sing. This krajappi has four coupled strings, seventeen frets on the neck and six on the soundboard. One of the characteristics of this orchestra is that both string players are represented as left-handed because the outfits are reversed.

Marriage of Prince Siddhartha with Princess Yasodhara

The hierarchy of the scene clearly appears from the bottom up: from the street to the Royal Palace. Seven musicians play in a dedicated space. The soundbox of the leaf-shaped krajappi is of the Bodhi tree. There are thirteen frets on the neck and seven on the soundboard. The pegs are organized as a cross and the four strings are clearly visible. If the krajappi player is right-handed, the fiddle player is represented as a left-handed player.

Prince Siddhartha leaves the palace where he grew up

This is the classic scene of the great renunciation, in which Prince Siddhartha leaves his wife and newborn son to seek to understand how to free humanity from suffering. Leaving the palace, he leaves the musicians and the dancers asleep. Then he meets four disguised divine messengers: an old man, a sick man, a dead man and a wandering ascetic, represented here as a monk.

The scene of sleeping musicians is, for painters, the opportunity to represent musical instruments that they themselves have seen in their socio-cultural environment. Depending on the cultural and intellectual level of the painter or his master, the choice of instruments and the quality of the details are variable. Here, one sees the neck of the krajappi, that of the fiddle and three other instruments emerging from the abandoned bodies.

Organological and musicological teachings of the Buddhaisawan Chapel's frescoes

These paintings are rich in teaching about instruments and musical practices of the late 18th century. First of all, these orchestras must be considered as palatine and non-popular ensembles. Here, women play the instruments. The reality of popular music is quite different. The ensembles are constant from one painting to another, demonstrating that this orchestral model is adapted to events and enjoys great prestige since it is at the service of the Buddha, the court and the aristocracy. There is doubt, however, about the use of this type of orchestra for the funeral of Princess Yasodhara.

The number of frets represented is certainly not reliable. On the other hand, it can be concluded that all the krajappi of the court, at that time, had four strings tuned in pairs to the fourth or the fifth according to tradition. This configuration provides the instrument with greater sound power and increased harmonic richness. Indeed, in music, 1 + 1 is not equal to 2. The slight phase shift that can result from a tuning difference between two adjacent strings creates harmonics that enrich the sound beyond the simple addition of the acoustic power of each of the strings.

The presence of female musicians at the court is in line with the court orchestras of King Jayavarman VII and probably other rulers, but we have no hard evidence about them.

The religious scenes depicted in this chapel also offer us a life touch at the court of Siam in the 18th century through costumes, customs, dances and musical instruments, all of which are absent from the iconography from Cambodia.

The krajappi through the iconography of a cabinet of the 18th century

An eighteenth-century cabinet of the Ayutthaya School, belonging to the National Museum of Bangkok, shows a musical ensemble conforming to those of the Buddhaisawan Chapel, but to which are added some more instruments. Thus, from left to right: an aerophone (oboe?), a pair of small cymbals, a gong chime, a barrel-shaped drum, a krajappi lute, a three-strings fiddle, a second aerophone (oboe?).

In the back of the cabinet, another krajappi player seems to be the clown!

The krajappi player of Wat Niwet Thammaprawat, 1878

The construction of Wat Niwet Thammaprawat was ordered by King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) in 1876 to serve as a royal temple at Bang Pa-In Palace. Built in neo-Gothic style, with stained glass windows and an altar, it is the work of the Italian architect Joachim Grassi. It looks like a Christian church, but its main image is that of the Buddha, instead of the crucified Christ. Its construction was completed in 1878.

This temple belongs to the Dhammayut Order of Theravada Thai Buddhism. Classified as a historic monument, it received the “Architectural Conservation Award” in 1989. It is located on an island of the Chao Phraya River.

In a niche at the end of the building is a musician playing krajappi. The instrument is very realistic. He has three pegs, a dozen frets (the first seems to be missing) and two strings.

This work is to be compared to the next, belonging to the National Museum of Bangkok.

Ancient krajappi

A few ancient instruments (late nineteenth, early twentieth century) documented and referenced as ‘krajappi’ belong to various museums around the world. Here are some links:

- Krajappi ref. 3096. Royal Museum of Art and History. Before 1913.

- Krajappi. Ref. 2333. Museum für Musikinstrumente der Universität Leipzig.

- Krajappi. Ref. 2004.415. Early 20th century. Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

- Two krajappi of Prince Paribatra. Suan Pakkad Palace Museum (See below).

Krajappi of Prince Paribatra

Two exceptional instruments (undated) are part of Prince Paribatra's collection. They are displayed in two windows of the “House I” at the Suan Pakkad Palace Museum in Bangkok. They are of exceptional dimensions. We could not take their measurements because of their inaccessibility, but their total length is of the order of 1,35m. Everything is excessive in these instruments: the thickness of the sound box and soundboard, the height of the frets, the width of the neck, the spacing of the strings, the length of the head. One of them is decorated with a mosaic of glass tesserae of green color but whose state no longer allows to admire the fair beauty. To get an idea, we can admire the instrument of Nattaphan Nuch-amphan called “Glass Krajappi” (see below). The peculiarity of these two krajappi also lies in the exceptional use of an easel like many other types of lutes around the world.

We will distinguish the two krajappi of Prince Paribatra by two distinct names: the “Simple Krajappi” and the “Glass Tesserae's Krajappi”.

The Simple Krajappi of Prince Paribatra

Most of the constituents of the Simple Krajappi seem original, with the exception of the frets which are the most sensitive part. Let us mention here that on four-string krajappi, there is no “anti-loss” thread, as is the case on the two-stringed chapei. The split soundboard has been consolidated. What we can notice is that on the instruments of the Museum of Music of Paris, the tailpiece was simply stuck on the soundboard. The only pull of the strings in the axis of the tailpiece made it possible to resort to a simple gluing. But here, the angle formed by the strings between the tailpiece and the top of the bridge creates a traction to which the collage does not resist. This is why the tailpiece was screwed into the soundboard.

The Glass Tesserae Krajappi of Prince Paribatra

All the constituents of Glass Tesserae Krajappi seem original except the frets; they are the same making as the Simple Krajappi.

Krajappi vs. chapei

We will compare here one of the instruments photographed by Émile Gsell, the instrument of the Musée de la Musique in Paris (ref. E.1177) and the two krajappi of Prince Paribatra belonging to the Suan Pakkad Museum in Bangkok.

A preliminary remark must also be made about the paternity of the instruments present in the photo of Émile Gsell opposite. The three-strings fiddle is more like the size of a Thai saw sam sai than a tro Khmer. The same goes for the goblet drum. We think that some of these instruments (chapei / krajappi, fiddle and goblet drum) were made in the Siam or Cambodia kingdom by a Siamese or even Khmer maker trained in Siam. The xylophone, the metallophone, the gong chime and the zither do not show any Khmer or Siamese particularism.

Comparison of the general shapes

We present below the chapei ref. E.1177 of the Musée de la Musique in Paris and the two krajappi of Prince Paribatra. The shape of the soundboxes is comparable. We can also bring them closer to Émile Gsell's photographies.

Comparison of the tailpieces

The general shape of the tailpieces and the central decoration are the same, with the detail. Here we can bring them closer to Émile Gsell's photo.

Comparison of pegboxes, heads and pegs

The pegboxes, heads and pegs are identical and we can, once again, bring them closer to the photo of Émile Gsell.

Provisional conclusion

When confronting the various organological elements, all these instruments seem to have been made by the same maker or workshop, Khmer or Thai. Then, as they are, on one side between Khmer hands and on the other, in Thai hands, the question arises: are they chapei or krajappi (according to the nationalist meaning)?

If we compare the various chapei individually photographed by Émile Gsell with those of other photographers, notably the instrument placed on the floor of Princess Kanakari at the beginning of the 20th century, we are dealing with instruments of the same generation considering some organological details: the head's curve, the four fine pegs, the frets stuck on the soundboard.

We can provisionally conclude that the instruments of the Court of Cambodia, at the time of Émile Gsell, and those of the Court of Thailand were of similar manufacturing. We can also say that there were, on the one hand, high-quality four-stringed court instruments and, on the other hand, more modest instruments made for musicians of the people by professionals artisans, the musicians themselves or their neighborhood. Let us mention that the manufacture of a chapei is not complex beyond measure and that a good carpenter, knowing moreover how to handle a turn (at the time a turn on foot), can manufacture it quite easily as soon as it possesses good wood species, a model and the advice of the musician. This last remark stems from our recent experience with a wood sculptor with no experience in the field of chapei, who successfully managed, in two weeks, to make a copy of an old instrument.

Krajappi's revival in Thailand

In Thailand, there is no longer any recognized practice of krajappi in the working class, as in Cambodia. However, a new awareness of the importance of culture in the context of globalization is now pushing both the Thai institution and isolated or organized individuals to restart a practice.

Concerning the instrumental manufacturing, old models are now used as stallions, either for an identical reproduction or as a source of inspiration.

We met Nattapann Nuch-ampann, a Thai artist and esthete who is keen on ancient culture, who has some remarkable contemporary krajappi inspired by ancient tradition.

Nattapann Nuch-ampann, a renovator

Nattapann Nuch-ampann (ณัฐพันธุ์ นุชอำพันธ์) started studying and playing thai music when he was around 12 years old. First, he played the saw duang fiddle and then the ranat xylophone. In high school, he won the first prize in khim zither national competition. Later, in Chulalongkorn University, he continued playing Thai music in Thai Music Club.

He has been interested by the krajappi at the end of the 2000s. He realized that this instrument was little by little disappeared from Thai musical practices. Anyway, in a little part of social media, there was a small group of krajappi lovers and they always discussed a lot about its playing technique, its tuning system, the manufacturers, etc. Every idea inspired him to find the good krajappi and made him dreaming one day playing this ancient instrument.

Until one day, he had a chance to know a krajappi maker in Ayutthaya province. He made it with care and good quality. Finally, he ordered a first one, and a second one… then four to this only maker.

But it was impossible to find a krajappi teacher because the instrument was not popular and disappeared from alive Thai culture long time ago. Nobody knew exactly how it was played. The last krajappi known player in ancient style was the royal consort of King Rama V reigning from 1853 to 1910. After that, it seems nobody played it.

So how to restart a disappeared practice? Nattapann Nuch-ampann says: “Nowadays we all play krajappi by imagination, including myself. Sometimes, I listen how the Khmer chapei players play, even techniques they use. As Thai and Khmer shared the same culture for centuries, I think it should be similar to ancient Thai way to play. However, I have melodies in my head, so I just play them as I think the way it should be.”

But Nattaphan didn’t stop at four krajappi. When we find him at home, he has eight instruments from different manufacturers.

In addition to being a musician, Nattaphan is an esthete. Each instrument ordered by him is a work of art and he takes extreme care. His aestheticism is also embodied in the place he offers his instruments. His music room and the various places he dedicates to music and the living arts in general lend themselves to a sensitive musical practice and quality cinematographic productions. Judge instead ...

Find Nattapann Nuch-ampann on his channel wisetdontree วิเศษดนตรี

The remarkable krajappi of Nattapann Nuch-ampann

We present here the most remarkable krajappi created by Nattapann Nuch-ampann himself but built by various manufacturers. Some have a name.

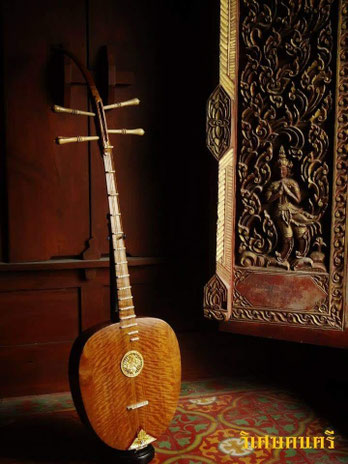

Mai Lai Krajappi

“Mai Lai Krajappi” means “Striped Wood Krajappi”. It was made of tabak wood by Chakri Mongkol in 2013 and decorated by Nattapann himself.

The pegs are made of wood and the strings of silk. The soundbox is ovoid. There is a rosette at the center of the soundboard and a bridge under the strings

Unnamed Krajappi

This “Unamed Krajappi” was made by Wannarat Suppasakuldamrong (general structure) and sculpted by Pornpol Sapsakul in 2015-2017. The soundbox is of jackfruit and the wooden handle of kaew. This is one of the highlights of the Nattapann Nuch-ampann collection. Acoustically and aesthetically, it's truly a masterpiece of the Thai musical instruments making.

Contemporary Krajappi

The Krajok Krajappi

The Krajok Krajappi, litt. “Glass Krajappi”, was inspired to Nattapann by the old instrument of the Suan Pakkad Museum described above and named by us “Glass Tesserae Krajappi”. The structure was built by Wannarat Suppasakuldamrong in 2014-2015 and the blue glassware and green decoration by Prapan Kaewwiset in 2016-2017. The soundbox and the neck are made of jackfruit. Like the previous instrument, this krajappi is a true masterpiece.

Krajappi with spring device

This instrument has, inside its soundbox, a spring device coming from an old western pendulum clock. Such a device is mentioned on the documentary sheet of the Musée de la Musique in Paris (ref. E.1177). However, when the instrument is played, there is no acoustic change; the internal device remains inert until the instrument is shaken. The soundbox is close to that of the instrument of the Musée de la Musique in Paris and also that of the Émile Gsell's photographs. The tailpiece has a sounder, that doesn't seem to have been the case on the old spring instruments of the 19th century.

Below, such a device is visible inside an old krajappi. It consists of four metal spindles fixed in the wall of the soundbox. Along each of them, a second solidary spindle ends with a spring supposed to hit the terminal part of the first one.

We recorded Nattapann Nuch-ampann spring krajappi but without tangible results. The setting vibration was perhaps related to a particular playing technique?

Nattapann Nuch-ampann playing a spring device krajappi

Krajappi with metal strings

The musician of this video, Suwat Utaekun, teaches in Buriram Province. He plays a krajappi with two metal strings. This configuration is atypical but deserved to be reported because the acoustic result is interesting. According to Thai ethnomusicologist Anant Narkkong, this type of “folk” krajappi is found in the Thai-Khmer community of Buriram-Surin-Sisaket region. Its making is more similar to the Khmer chapei than the instruments described above, even if the terminology used in the title of this YouTube video is “กระจับปี่ krajappi” ...

See also:

The “Lesson of the three strings”

The arak ensemble of the Wat Reach Bo

The chapei players, by Émile Gsell

The chapei of the Musée de la Musique of Paris

Edited by Cambodian Living Arts, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

© Cambodian Living Arts 2018-2023, © Patrick Kersalé 1998-2024