The chapei of the Musée de la Musique of Paris

We wanted to devote an entire article to one of the oldest chapei / krajappi that came to us. It is the property of the “Musée de la Musique” of the “Philharmonie de Paris”, referenced E.1177. We have also mentioned this instrument in our article The chapei players, by Émile Gsell given its historical importance.

The image opposite shows the original label glued to the back of the soundbox: “1177 Guitar of Cambodia”.

The instrument was acquired by the museum on December 25, 1887. To access the MSDS of the Museum, click here.

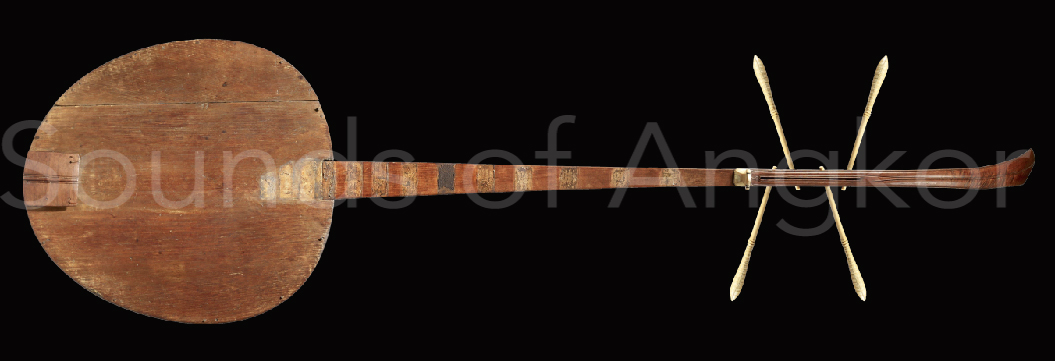

A first description of the instrument was made in Léon Pillaut, 1er supplément au catalogue de 1884, Paris, Librairie Fischbacher, 1894, p.58 (the catalog of the collection of the Instrumental Museum of the Conservatory drawn up at the end of the 19th century): “1249. - Chiapey. This large Cambodian guitar is 1.5m in total length; the heart-shaped soundbox is 0.41m and a half high by 0.39m wide and 0.06m cent. thick. The elegantly curved handle at the back carries 13 frets. 4 long and thin ivory pegs stretch the strings. This beautiful instrument is usually part of the Cambodian orchestra. ”

Alexandre Girard-Muscagorry, Curator in charge of non-Western music and culture (Cité de la Musique, Philharmonie de Paris) exhumed from the museum's archives (preserved in the National Archives, call number AJ37 321, 6b) this letter dated December 30, 1887 mentioning the instrument under the name “great Indian guitar”. If the author of this letter, Mr. Boilesne, was for a time the owner of the instrument, he seems to have lived at 22 rue de la Pépinière, Paris 8e.

Organological characteristics

This instrument is first of all a great beauty despite its sobriety. It is made of red wood whose exact nature remains to be determined. Its monoxyle soundbox has a perfectly symmetrical ovoid shape. It originally had thirteen frets (ten stuck on the neck and three on the soundboard). The soundboard is full, that is to say without orifice or rosette. The strings were made of silk, the nut and the residual peg of ivory. The curvature of the head is the result of a bandage and not a sculpture in the mass (the head is moreover in the axis but shows a slight deviation). This parameter is important because the total linear length is decisive in the arithmetic symbolism of the instrument.

The decor at the back of the soundbox

The back of the soundbox is decorated with a beautiful naughty image. Khmer modesty (although at that time the women were still going barefoot) was not achieved because this part of the chapei was not visible to the public.

In the center of the image is a tiny hole whose role could be to allow air to circulate between the outside and the inside of the sound box. Note, however, that no hole is drilled in the soundboard, contrary to more recent and contemporary practices.

The scene shows Hanuman, the chief general of the monkey army in the epic of Rāmāyaṇa (Reamker Khmer រាមកេរ្តិ៍ / Ramakien Thai รามเกียรติ์). He is courting Princess Benyagai (Vibhishana), daughter of Prince Phiphek, after playing an unsuccessful trick on Prince Rāmā.

Restauration

In 2016, Christian Binet restored the instrument. We were able to consult the report. At the origin, it was fouled, the neck disengaged from the soundbox and the tailpiece off. The edge of the soundbox was broken at the junction of the neck. The intervention consisted in cleaning the surfaces, putting back the neck and picking up the tailpiece.

Originally, the neck was held by a key with a tenon inside the body.

According to the restorer, the neck was probably torn off its seat after a shock, causing the edge of the soundbox to deteriorate. To optimize the restoration, it was decided to open the instrument by separating the soundboard from the soundbox and repairing what could be. However, given the weakness of the elements of this area, it was decided to stick the handle to distribute the mechanical forces. Fish glue was used.

The soundboard was attached to the soundboard by hardwood and bamboo spikes.

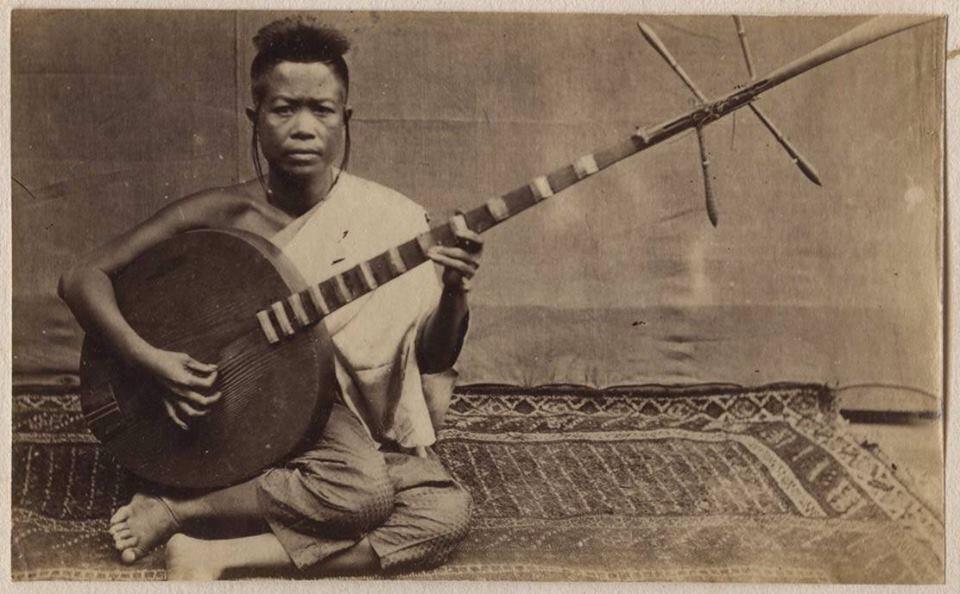

Noisemaker

The opening of the soundbox revealed the existence of a noisemaker composed of rods and springs. Only three springs remained, but visible holes in the soundbox splints suggest that other springs previously existed. Such a device seems to have been the norm in the second half of the nineteenth century and perhaps even in the early twentieth century. Pictures of a Thai krajappi below prove it. A recording made with a contemporary instrument, recreated on the basis of ancient instruments, did not show any real acoustic effect. Only the shaking of the instruments makes it possible to hear the interlocking of the metal parts (see the two videos below). Perhaps this is just a question of adjustment between each rod and the associated spring. A reconstruction of the instrument of the Musée de la Musique of Paris could provide an answer to this question ... (To be continued).

Chapei E1177. Sound produced by the springs when we shake the instrument.

Nattapann Nuch-ampann plays a “springs krajappi” but there is no particular acoustic effect.

The enigma of the inscription

During the restoration of the instrument in 2016, a surprise awaited the Christian Binet. The interior of the soundboard contained an inscription and a drawing that the present study attempted to decipher. There are several distinct ensembles; some of them seem complementary.

Poem in Thai language

Une inscription en langue thaïe, de couleur noire, se répartit de part et d'autre du pourtour de la table d'harmonie. Il s'agit d'un poème dans un style propre au XIXe siècle, déchiffré et traduit par Theerapat Sinthudech :

A Thai inscription, in black, is distributed on both sides of the perimeter of the soundboard. It is a poem in a style of the nineteenth century, deciphered and translated by Theerapat Sinthudech:

เขาจะเล่า เล้าแม่อย่าขาน

อย่าจำนรร มั่นคงหนัก

No matter he tries to lure you,

Do not reply, not even a word.

This message seems to make sense in relation to the central drawing (hereinafter) which shows a woman looking away.

Design

On the original document (above) a drawing, in white, depicts a woman turning her head. She seems to raise her arms in the manner of a dancer.

We propose here a blue color treatment to better show the contours.

Scattered Thai characters and words

We have numbered from 1 to 9 the alphabetic characters and the scattered Thai words of black color. Theerapat Sinthudech gives us a first decoding, without it being possible for the moment to find a semantic logic between these various elements.

1 : เยด

2 : ทง

3 : ทน

4 : ท / ก

5 : เอน

6 : เรอน. Old spelling of the word “house” today spelled เรือน. At that time, this term was commonly used as a female given name. A question arises: could this name have been that of one of the chapei players of the Cambodian court, if we are to believe the provenance indicated on the museum's label?

7 : ข

8 : ท

9 : เขาจ่เลน. Nowadays, this term, spelled เขา จะ เล่น, means “He/she will play”.

A Khmer character?

The white character in the center of the red circle, could be the Khmer letter ម (upside down). It was once pronounced “ma”, today “mo”. But it could also be, coincidentally, only the bun of the woman.

To understand why the message is in Thai while the instrument seems to come from Cambodia, let's go back briefly to the common history of the kingdoms of Cambodia and Siam. From the 15th to the 19th century, Cambodia saw a long political decline under Siamese rule, apart from a brief period of prosperity, in the 16th century, during which the rulers, who built their new capital at Longvek, trade other parts of Asia. From the beginning of the 16th century, Cambodia became a vassal of the Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya. In 1861, King Norodom I was expelled from Cambodia by a rebellion led by his half-brother Prince Si Votha and took refuge in Siam. On April 23, 1863, this same sovereign proposed to French lieutenant Ernest Doudart de Lagrée an agreement by which he would agree to establish a protectorate of France over Cambodia. On August 11, the king ratifies the treaty. In 1866, Norodom I transferred the Oudong court to Phnom Penh. On July 15, 1867, Siam renounced its rights over Cambodia and recognized the French protectorate. In return, he obtained the provinces of Battambang, Siem Reap and Sisophon.

If, in the 19th century, Khmer was the main language of the court and royal administration, some members of the court spoke and wrote Thai; some went to study to Siam.

Among the artists of the Royal Palace of Cambodia, there were probably also Siamese musicians and dancers, teachers or performers.

Who was the owner of this instrument?

We don't have any tangible element to answer very exactly such a question, but we can advance the hypothesis that it belonged to a woman of the court (of Cambodia?) And this, for several reasons:

1. Compared to the large size of both Prince Paribatra's krajappi, this one is a small instrument that seems indicate it was played by a woman.

- The various photographs of court musician made by Émile Gsell around 1866-70 show similar instruments probably from the same workshop as that of the Musée de la Musique in Paris. Remember that the E.1177 instrument was purchased in 1887, a period consistent with that of the photographs.

- The set of instruments offered in 1930 by King Sisowath Monivong to King Prajadhipok (Rama VII) of Siam during His visit to the Court of Cambodia included two chapei of the same making, a small and a large, which we interpret respectively as a woman and man instrument. In addition, another instrument studied by us, from the court of King Sisowath Monivong was appraised by the Chum Prosar maker as a woman's chapei.

2. The inscription and the drawing inside the soundboard make sense. Indeed, the poetic inscription in Thai language, associated with the drawing of the woman who looks away, constitute a message calling women to be wary of the behavior of men.

3. It can only be a musician of the court because at the end of the 19th century, it seems unimaginable that a woman of the people plays such an instrument. In addition, the first name inside the instrument is feminine.

4. The back of the soundbox where Hanumān is seen grasping the breast of Princess Benyagai (Vibhishana) can, however, be interpreted in the light of the inscription and the drawing as a warning against male behavior.

Where was this instrument made?

In comparison with the previous information, on the one hand, the similarity of the two krajappi belonging to the Suan Pakkad Museum in Bangkok, described in the chapter “The Thai krajappi”, and representations of the photographs of Emile Gsell on the other hand, we think that the E.1177 instrument was manufactured in Siam by a renowned maker. The instrument we called “Glass Tesserae's Krajappi” demonstrates that the workshop was able to make prestigious instruments for the royal courts of Cambodia and Siam (assuming of course that the glass tiles were laid in the workshop and not elsewhere).

In summary, we have today (October 2019) knowledge of the real and virtual existence of five chapei / krajappi from the same workshop: the two instruments photographed by Emile Gsell at the court of Cambodia around 1866-70 (those visible on both other photographs of the orchestras are the same), the two instruments of the Suan Pakkad Museum in Bangkok (date unknown but probably second half of the 19th century), the instrument of the Musée de la Musique of Music acquired in 1887 (see photos below) .

Acknowledgment

The study and the expertise of this instrument were made possible thanks to the collaboration of an international team coordinated by Patrick Kersalé. May everyone be thanked (in alphabetical order):

- Christian Binet - Restorer of the instrument

- Philippe Bruguière - Ex-Curator at the Musée de la Musique - Cité de la Musique - Philharmonie de Paris (France)

- Alexandre Girard-Muscagorry - Curator at the Musée de la Musique - Cité de la Musique - Philharmonie de Paris (France)

- Claude Germain - Photographer - Cité de la Musique - Philharmonie de Paris (France)

- Émile Gsell - Photographer (Vietnam, Cambodia, France)

- Frédéric Gsell - Informant

- Christine Hemmy - Assistant Curator of the Musée de la Musique - Cité de la Musique - Philharmonie de Paris (France)

- Yann Minh Kersalé - Videographer (France)

- Katia Kolobaeva - Medium (Russia)

- Anant Narkkong - Ethnomusicologist (Thailand)

- Nattapann Nuch-ampann - Musician specialized in krajappi (Thailand)

- Theerapat Sinthudech - Faculty of Archeology (Thailand)

- Trent Walker - Specialist in Buddhist Literature (USA)

See also …

The “Lesson of the three strings”

The arak ensemble of the Wat Reach Bo

The chapei players, by Émile Gsell

Edited by Cambodian Living Arts, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

© Cambodian Living Arts 2018-2023, © Patrick Kersalé 1998-2024